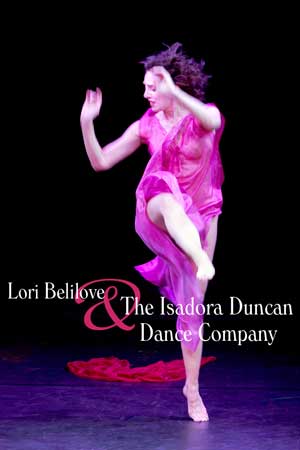

Lori Belilove

Founder, Artistic Director and choreographer of The Isadora Duncan Dance Company & Foundation & Soloist, is recognized around the world as the premier interpreter and ambassador of the dance of Isadora Duncan. She is sought after as a unique contemporary artist who understands the essence of Isadora. Known as a solo dance artist for her interpretations of Duncan’s signature solos and staging of Duncan’s group masterpieces, she has also been recognized for creating powerful, contemporary works in her own voice. The purity, timelessness, authentic phrasing, and musicality of Duncan dance has been passed down to Ms. Belilove through a direct line of Isadora Duncan dancers. Among her first teachers were first-generation Duncan dancers Anna Duncan and Irma Duncan, two of the six adopted artistic daughters of Isadora. She was trained extensively and coached for performance by second-generation Duncan Dancers Julia Levien, Hortense Kooluris, and Mignon Garland. Since the age of twelve, she has pursued her passion for modern dance, training primarily in the San Francisco Bay Area and New York. For years she trained in the modern technique of Doris Humphrey as a private student of both Eleanor King and Ernestine Stodelle. Ms. Belilove is the leading dancer in the award-winning PBS documentary, “Isadora Duncan: Movement from the Soul,” narrated by Julie Harris. Touring extensively both nationally and internationally in Brazil, Korea, West Africa, Canada, Mexico, and Europe – as a master teacher, she has taught at many universities and colleges including Harvard University, The Juilliard School, Northwestern University, Smith College, University of Alabama, Ohio State, UC Berkeley, Drexel University and Franklin & Marshall.

Founder, Artistic Director and choreographer of The Isadora Duncan Dance Company & Foundation & Soloist, is recognized around the world as the premier interpreter and ambassador of the dance of Isadora Duncan. She is sought after as a unique contemporary artist who understands the essence of Isadora. Known as a solo dance artist for her interpretations of Duncan’s signature solos and staging of Duncan’s group masterpieces, she has also been recognized for creating powerful, contemporary works in her own voice. The purity, timelessness, authentic phrasing, and musicality of Duncan dance has been passed down to Ms. Belilove through a direct line of Isadora Duncan dancers. Among her first teachers were first-generation Duncan dancers Anna Duncan and Irma Duncan, two of the six adopted artistic daughters of Isadora. She was trained extensively and coached for performance by second-generation Duncan Dancers Julia Levien, Hortense Kooluris, and Mignon Garland. Since the age of twelve, she has pursued her passion for modern dance, training primarily in the San Francisco Bay Area and New York. For years she trained in the modern technique of Doris Humphrey as a private student of both Eleanor King and Ernestine Stodelle. Ms. Belilove is the leading dancer in the award-winning PBS documentary, “Isadora Duncan: Movement from the Soul,” narrated by Julie Harris. Touring extensively both nationally and internationally in Brazil, Korea, West Africa, Canada, Mexico, and Europe – as a master teacher, she has taught at many universities and colleges including Harvard University, The Juilliard School, Northwestern University, Smith College, University of Alabama, Ohio State, UC Berkeley, Drexel University and Franklin & Marshall.

What are you currently working on?

What are you currently working on?

This year we celebrated Isadora’s 135th birthday on May 27th. We had a huge gala and proclaimed it Isadora Duncan week. There is also a U.S. postage stamp coming out honoring innovative choreographers including Fosse, Katharine Dunham, Limon, and Isadora. We’re having new premieres of Isadora’s work. I hope to take them to some colleges. Isadora’s a national treasure.

How did the way in which you were raised have an effect on your becoming a dancer?

I was sort of a tomboy growing up. I did all the athletic sports. I was challenged with all kinds of notions of what fine art was. I did pottery, gardening, floral design, sewing; my mom was a gestalt therapist and a great homemaker. When she wasn’t busy with her hands, she was very social. My dad was a unique individual – a businessman, and also sang opera. So my brother and I were raised in a way that allowed us great exploration out in Berkeley, California. All our friends were unique, writers, different kinds of business people, free thinkers, forward thinkers, college students.

Isadora Duncan said she danced in the womb, having been nourished on oysters and champagne. I guess I would say I began by being nourished by dancing when I was young. Late into the night I would practice to the music of our player piano; I was about eight. I explored movement for movement sake. I had a lot of pets and animals and spent a lot of time out of doors; I loved nature. We had gardens, a creek that turned into a waterfall; I thought I had found a miracle land. It was all quite extraordinary. I explored everything, in a sense, educating myself.

What led you to first learn about Isadora Duncan and how would you describe the effect that had on you?

When we first went to Europe, it was an eye-opening experience. It was a lot of fun, traveling all over London, France, Germany, Luxembourg, Italy, Switzerland, and then we arrived in Greece I felt so at home. The Duncan family had also come to Greece to make their pilgrimage.

While I was there I met an older gentleman who told us he had been a member of her troupe; he was about seventy, and everything he said had a deep impact on me. I began to learn everything I could about Isadora.

When I got back to America, there was a lot of unrest and it was getting really rough socially, in Berkeley. I lived inside all of it. My mother thought I should go to the country to a small Quaker boarding school; she thought I was growing up too fast and wanted me find my authentic self. I agreed to go, and once I was there I felt a tremendous freedom. I was there for two and a half years. I started to study the ideals of Isadora of passion and freedom. I decided to go back to Europe, to Greece, and met Mr. Carnelis again, and together we would visit many of the ancient ruins. I took dancing and singing lessons. He told me about Isadora and showed me a locket which held a lock of her hair, He said to me: You are the next Isadora,” and gave it to you. He told me I needed to come back and study with him when I was ready. I was in heaven.

When I think about it, that trip had a huge effect on me. I had read Isadora’s autobiography when I was twelve, and she fascinated me. I was also reading a lot of literature and poetry and began to develop a classic sense of understanding beauty and harmony.

For me, Isadora’s artistic sensibility, her passion for life is how we should all live. It offers a pathway for living; a very full way to be. In a full-bodied way, natural, and to allow that to occur naturally through movement. Her dance, her style comes from the breath and the solar plexus and the movement of the torso. The seed of our tremendous internal force allows for huge emotions and power and she offered the world how to access it.

I began studying with everyone to understand how to do it. I went to the ends of the world to keep meeting those who had worked and studied with her, coming upon fragments of her choreography.

When I got back, there was a knock on the door and a woman was standing there. She introduced herself and told us she had actually been in Isadora’s troupe, and then told me that the gentleman I had studied with Greece was an imposter. He had never been with Isadora. He had thought everyone was dead so he thought he could get away with it. It was shocking. He had offered tremendous things, but he had never been in her troupe or known her.

She told me she really didn’t care about him, she was much more interested in keeping Isadora’s work alive because there was no Isadora dance school, and so much had been lost.

I decided to study with her and although it took a long time, it led me to Irma Duncan, and the New York clan of Isadora’s followers. I was embraced by them but they were teaching in small studios and I wondered: There’s a technique, with over 80 dances but everyone knows the same dance. How could Isadora’s spirit and form come alive when it was only through fragments of what it once was?

I decided to gather together this body of work and understanding and began to figure out how to teach it to young students, to a modern dancer or a girl on point. I trained a lot of young people and wanted to start a new company, and impart the work for a new generation. I had my base; I was a Isadora Duncan dancer but I also gathered from other styles to add to the work, eventually creating my own work. Basically, the mantle folded onto me, and those who came before me became my advisers and coaches.

So you found a way to bring her work into the present?

The link to the present is a passage into modernity, a link into art and dance, from one another, from sculpture to painting, from philosophy to music, she wanted all arts to move forward, to work with each other. She’s also so important in how she approached education, wanting to reform the way to reach young people. So gentle, so loving.

She had gone back to the Greeks, to understand and respect the old traditions and take the riches they had to offer and then bring an openness to the movement of the body, and what is also worn over the body. So allow a free-flowing movement. Of course, they thought she was mad to show loose breasts and naked legs. But they fell in love with her passion. Her dances expressed the human condition – classic and very humanistic. I love her work. It feeds me and churns inside of me.

Why did teaching become important for you?

Because I felt dancers needed to connect with themselves with a bigger world and to go deeper inside themselves, to explode off the floor, to gain a deeper, dramatic sensibility.

When I had come back from Greece, within six months I had started teaching a children’s class. Then after I had met the different Duncan dancers I wanted to share what I had learned, so from that time it’s been calling.

How do you create new work using what Isadora’s choreography?

It may take me six months to create a new piece. I love exploring ideas and then, as I’m living my life sometimes, when the planets converge, usually in the deep hours of the morning, something comes in and then something is triggers deep inside, and then it becomes like a faucet. The synapses snap and one thing leads to another and then I plan rehearsal time with the company.

I had the great fortune of receiving a residency in Florida at the Atlantic Center of the Arts to create new work for three weeks. That’s when “The Every Woman” series emerged into a fuller form.

When you’re working on a new piece, when do you know when it’s become what you envisioned?

It can exist in one fleeting moment of time: the structure, the narrative, the story of what the dance is built, the actual pattern, they all converge and the statement is made. Maybe it becomes clearer during rehearsals and then you can videotape and you have that version to examine. Of course, it was done at that moment and can never been done exactly the same but I can re-visit it. It has to come back to life in a more refreshing way and then it may take on some other variations.

When I began to steep myself in dance history, I saw how Isadora changed movement, how she had moved away ornamental dancing, moving into more of an abstract ballet, opposite in a way from Fokine and traditional ballet. She was breaking tradition. Watching the work of Nijinsky blew me away and I could see how deeply we can feel.

What is like to you when you enter into the state of creativity?

It’s very consuming, engaging my entire being. The act of it puts me in a state of complete playfulness and things almost appear a little differently. I see variations of things stumbling upon themselves. When I get into that creative state, the synapses pull you. I can spend an hour and it’s a fun state, you can crack jokes. I like to be there more than anywhere else. Once you’re there, you’re not afraid of who you. You’re skimming along a wave, on top of the water, there may be a splash, but you get up and you can find yourself in another place. I thoroughly enjoy that state. I try and find myself in this state as much as I can.•