Speech To The American Council For The Arts

I LIKE BEING A PLAYWRIGHT, which is fortunate, since that’s one of the few things that I can do with any competence. And it is nice to be able to pass your life doing that which you feel that you might be doing with some competence, and possibly, possibly even communicating with a few people. Because the function of the arts, is it not, absolute communication – to put us in greater contact with ourselves and with each other, to question our values, to question the status quo, to make us rethink that which we believe we believe.

One of the things that worries me so much about this civilization we call the United States – or at least as Max Lerner was kind enough to call us a civilization – one of the things that worries me most about the civilization of the United States is whether or not we are one of these bizarre civilizations that may be on its way downhill before it has ever reached Its zenith.

All civilizations have a duration. All civilizations have a period of enormous vitality, and then a kind of coasting status, and then eventually they began to subside, sometimes violently and sometimes merely with a whimper.

I worry sometimes that the American civilization may be on its way downhill.

I think one of the reasons that I concern myself, perhaps more than a number of other writers do, with the state of our societal and cultural health has to do with the time in our history that I became a functioning writer.

In the early 1960’s in the United States, we believed that just about anything was possible. We had gone through the years of Eisenhower’s “non-presidency.” We then had John Kennedy as our president. Youth, vitality, vigor, and the arts were burgeoning, at least in the major cities of the United States; they were vital and exciting.

In 1955, for example – and I looked this up – of the four most performed playwrights in the United States, all of them were dead. Eight years later, of the four most performed playwrights in the United States, three of them were living playwrights.

At the time I sort of emerged on the scene, the paperback book market had come into existence in the United States. People were able to get finally, for very little money, not only the classic works of world literature, but also the avant-garde works from Europe and Asia and the United States.

People began going to concerts of serious contemporary music. Finally there were more people sitting in the audience at these concerts than there were performing onstage. Museums and galleries were beginning to show the work of tough young artists, and people were looking, and people were paying attention. It was an enormously exciting time to be involved in the arts in the United States.

And in this period, for reasons that I like to think were rational – but perhaps were merely an accident – the National Endowment for the Arts was born.

I am convinced that the National Endowment for the Arts was created in the understanding that, unless we provide an aesthetic education for the people of this country, we are not doing our job; that unless we provide an aesthetic education for the people, we will be raising a society of informed barbarians.

And so the National Endowment for the Arts was born, pouring millions and ultimately hundreds of millions of dollars into the aesthetic education of people of this country.

The attempt recently on the part of the Congress of the United States to dismantle and ultimately destroy the National Endowment for the Arts, to destroy the aesthetic education of people of this country, worries me greatly because it tells me far more than I am comfortable to know about the state of our moral, philosophical, psychological, and ethical health; because these people who are voting to destroy the aesthetic education of the people of this country are doing it because we as a society have put them in the positions of power to do it.

So it is not their fault; it is ours.

There is a good and a bad side to everything. Two steps forward, two steps back, usually, in a participatory democracy, though I wonder sometimes how participatory a democracy are we.

In this last e1ection, forty-nine percent of the electorate voted, which means that you and I are being governed by the will of approximately twenty-five and a half of the potential electorate.

This is not participatory democracy. It is a kind of reverse elitism, and this worries me greatly as well.

Do we care so little – do we care so little about how we are governed that we don’t even bother to take care to see that we are governed rationally and intelligently?

Have we become so passive a society? Are we indeed dying in life? Have we become so passive that we will lose this enormously fragile thing called democracy?

I travel around a lot, and have, over the years. And over the years I have spent a lot of time –especially in the bad old days before the collapse of the Soviet Union – in Eastern Europe. I have spent time in other totalitarian societies as well.

But I spent a lot of time in the old Soviet Union going back to 1963, when John Steinbeck was kind enough to drag me along when he was part of the cultural exchange program. And he was asked, bring a young American writer with you, and John took me.

Over the years I have been to the Soviet Union with a number of writers I admire, including Bill Styron. He and I spent time together in Moscow.

Arthur Miller and I have spent a lot of time carrying placards, marching in front of the Soviet Cultural Ministry and the UN delegation in New York to protest the arrest of the writers and other people who dare disagree with their government in the Soviet Union.

So I have spent a lot of time in totalitarian societies, which has probably made me even more wonted about the passivity of the United States than I would be without that particular information.

The first time I went to the Soviet Union, I met a lot of people – dissident writers, quasi-dissident writers, and also the cultural commissars, the people who decided at that time what frame of reference the Soviet citizen would have to contemplate reality, who decided which novelists would have their novels published in addition to two million, and which novelists would be sent to slave labor camps, who decided which painters would have their paintings exhibited in the Tretyakov Museum in Moscow, and which ones, if they dared having an open-air exhibit of abstract painting on the banks of the Moscow River, would see the tanks come and bulldoze their paintings into the river; the cultural commissars who decided which composers would have cushy jobs at the conservatories and which ones, if their music was too adventuresome, would find themselves out of work: the people who decided what consciousness the Soviet citizen was able to develop.

One of the young writers that I met in my first visit to the Soviet Union was a young man named Andre Amalrik. He eventually spent several years in a Soviet jail for having written a book called Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984?

He was not far off.

He is dead now, alas. After he was finally thrown out of the Soviet Union, he was killed, very oddly, one midnight in northern Spain on a lonely road. He was on his way to monitor the Soviet noncompliance with the Helsinki Accords.

Back in 1963, he and I met on a snowy night in Moscow and spent a long time talking. And one of the things that he put forward to me was a theory he had that it was the intention of the people who ran the culture in his country to create what he referred to as a semantic collapse between our cultures, to create a situation where it would be impossible for communication really to exist, a total breakdown of language, a total breakdown of intention and of semantics.

Well, I had done my homework. I had read my George Orwell. I knew what he was talking about. But it was interesting to hear it in the mouth of the lion, so to speak.

I went back to England a few weeks later and began to think of it, about what Amalrik had told me. And I began to wonder. This semantic collapse that he was talking about, was this possible only between two such different societies as the United States and the Soviet Union, or wasn't it as least theoretically possible that there could be an ultimate and total breakdown even in the United States between those tough truths the intellectuals and the creative artists who wished to tell the people about themselves, and that which the people of the United States were willing to listen to?

And then it occurred to me even more – and it is a feeling that been growing in me all of these years – that, yes, such an antic collapse in the United States is not only possible, but I that it is occurring more and more. I find that we are in the middle of this particular kind of semantic collapse, and it worries me greatly.

Mind you, I would rather be a writer in the United States than in any other country I know of. And I have been to a lot of countries, and I have seen what creative people have to put up with.

The hostility, the occasional hostility, the occasional intentional misunderstanding of one’s work, the occasional dismissal of one’s work in the United States, is nothing, nothing compared to the literal life-and-death matter of daring to write the truth in a totalitarian society.

We are children compared to what other people have to put up with. I have seen creative people in totalitarian societies risk their very lives to read a book.

We don’t do that in this country.

There is in this country yet no one to tell us, no, you may not read that book; no, you may not listen to that string quartet; no, you may not look at that painting; no, you may not read that poem; no, you may not see that play; no, you may not read that magazine or that newspaper.

There is nobody in the United Stated yet to deny us access to the metaphor, if you will, access to the education that the arts can give us in this country; no one except ourselves.

The self-censorship, the abdication of participation on the part of so many people in the United States, is a form of death in life. It is a form of not participating fully in one’s own life. It is indeed a form of death in life.

Of course people can easily say, so what? What does it really matter? Here he is running on about the responsibility of people to the arts. Haven’t we had a rather rough twenty-five years or so in the United States? Haven’t we had the presidency disgraced by Mr. Nixon? Have we not had the fabric of our society torn apart by the war in Vietnam?

Have we not had younger people for many years now turning off from voting, turning off from participating politically in our society?

We are the only democracy that I know of where the college age students are not at the involved, informed political forefront.

We live enormously dangerously as a society. Our economy, as a result of eight years of the Reagan disastrous mismanagement, gives the false illusion of being a healthy economy.

Many things have been going wrong in this country. So why should we concern ourselves with anything so unimportant as the relationship between the arts and the rest of the people of this country?

Well, I can give you a couple of reasons why I think we should. One of them has to do with what it is that distinguishes us from all the other animals.

If there are a few creationists among you, I hope you will forgive that word “other.” But there it is.

There is something that distinguishes us from all the other animals. It used to be thought for a long time that we were the only animal that could efficiently use tools. But the more we began to look around us, we discovered that other animals could use tools just as efficiently as we did – but nowhere near as destructively of course – there are not very, very many animals who use weapons to kill their own kind.

We are one of the very, very few that has managed that advance in civilization.

It was thought for a long time that perhaps we were the only animal capable of constructing and maintaining a complex society. But the more we began to look around and see the societies of termites, of ants, bees, and other creatures, we saw that they were capable of maintaining a society at least as complex as that of Mainland China, and perhaps not as cruel.

It was thought for a while that perhaps we were the only animal possessed of – what is it called? – an immortal soul.

Well, whenever I hear that, I am reminded of the remark that I hope is not apocryphal, made by a – I can’t remember who it is late-nineteenth-century French Catholic novelist, who said, if I may not be with my dog in heaven, I will not go.

And those of us who have passed so much of our lives in the company of Irish wolfhounds know that the concept of the soullessness of other animals is preposterous nonsense.

Let me give you what I consider to be the one thing that really does distinguish us from all the other animals. And it is simply this:

We are the only animal who consciously and intentionally create art. We are the only animal who has invented the metaphor, the arts, to define consciousness to ourselves, to define ourselves. We are the only one that does this.

Now, I know about all of these experiments that have been made for the past twenty years with gorillas and chimpanzees, our persuading ourselves that they wish to be communicated with language and that we are capable of doing it. They figured out soon – quite soon – that gorillas and chimpanzees – all female, by the way –that the only gorillas and chimpanzees who even wanted to think about talking to us were female. I have no idea what this means.

But it was soon discovered that they did not wish to communicate vocally. They wished to use their vocal chords for far more sensible things like shrieking and screaming and yelling.

But a number of these female chimpanzees and gorillas were willing to learn a kind of sign language with us, to communicate with us by sign.

Some of them, I am told, some of these lady chimpanzees and gorillas, have developed a vocabulary in excess of five hundred words. This is certainly a far larger vocabulary than that of many people I have met in New York City.

But to my knowledge, with this vocabulary – and certainly a vocabulary that a number of playwrights I know find sufficient to write with – as far as I know – none of these lady chimpanzees or gorillas has yet written a play.

Now, I am sure that as soon as one does, given the state of our theater, it will be performed on Broadway at once. And given the state of our majority criticism, it will probably run for four and a half years, since our theater audiences, at least in the major commercial arenas, go to the theater merely when they are told to, not because it is something they think they might possibly learn something from.

But until this first lady chimpanzee or gorilla writes this first play and I get to have a chance to talk to her, for which I will be happy to learn sign language, and she convinces me that she did it on purpose – it was not monkey-on-the-keyboard, so to speak – I hold that we are the only animal who has invented and uses art as a method to communicate ourselves to ourselves.

And I am convinced that this has a great deal to do with evolution; again, my apologies to the creationists.

I was very happy to read that the Pope has decided there may be something to this whole theory of evolution.

I am convinced that the invention of the metaphor, the invention of art, if you will, is part of the evolutionary process.

We all used to have a tail, you know. Well, it wasn’t one gigantic community tail. That would be very restricting. But we all used to have our own tails. There is – take it on faith – at the base of your spine a little jut of bone called the coccyx, I believe. This is the vestigial remnant of your tails.

Now, to simplify only slightly, I think this is what happened: somewhere along the line, our tails fell off and we developed art. We developed the need and the ability to be able to hold an accurate mirror up to ourselves, to observe ourselves, to observe our behaviors, to observe our intentions; and there from came evolutionary development of art.

And we live in one of the few civilizations, one of the few societies where we are permitted practice evolution without cavil and without restraint.

As I said, there are no commissars sitting on top of us, saying you may not do this.

But the particular kind of censorship of our own self-awareness and self-knowledge that we tolerate and permit is shocking and makes me worry greatly about our civilization.

Democracy is enormously fragile. Other countries have learned this, that democracy that is not participated in fully and totally is in great danger.

I was pleased, if slightly surprised, to read this morning in “The Chicago Tribune,” an article agreeing with some of my theories, an article which suggested that our passivity, our lack of sense of responsibility to ourselves and to our fellows, is dangerous and destructive to democracy in the United States.

The late Diana Trilling, in one of her last utterances, remarked that we no longer have rational discourse, rational angry discourse in the United States.

She may have been talking about something that went out the window when her husband died. And while I do not wish to bring Lionel Trilling back from the grave, nor Diana Trilling for that matter, I think she had something there.

We do not have rational contentious discourse in the United States. The last time we had a political debate on the national level in the United States, a free-wheeling debate where the candidates were permitted to question each other, to talk without interruption and without stage management, was in 1960, in the debates between Kennedy and Nixon.

The rest have been stage-managed. The rest have been controlled to the extent that we learn absolutely nothing about the humanity or even the ideas of our candidates. We tend to vote more often because the “spill doctors” tell us how we reacted before we have had the opportunity to react ourselves.

It is part of the growing and continuing passivity of us as a society. The middle-browing, if you will, of American culture is the result of commercial need, and absolutely nothing else.

It is not a democratizing of culture in the United States. It is the mass cultural selling.

We hear terrible terms of approbation these days, like elitist, liberal, thinking.

Worry about it. Worry a good deal about it. •1995

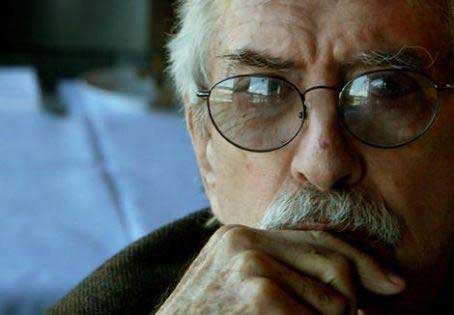

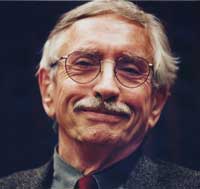

Speech given by Edward Albee to The American Council for the Arts. Printed in Stretching My Mind: The Collected Essays of Edward Albee. Published by Carroll & Graf. Reprinted with the permission of Edward Albee.

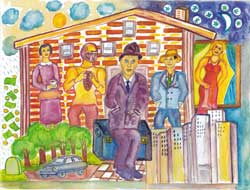

Drawing above reproduced by special arrangement with Hirschfeld's exclusive representative, The Margo Feiden Galleries, NY.

EDWARD ALBEE, recognized by many as one of America’s greatest living playwrights, his many works include “The Zoo Story” (Drama Desk award, Vernon Rice Award), “The Sandbox,” “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” (selected by the award’s grand jury for a Pulitzer, but overruled by the advisory committee – the play received the Tony Award in 1963, and for Best revival in 2005). He is a member of the Dramatists Guild. He has received Pulitzer Prizes for Drama for “Seascape” (Tony award, Drama Desk Award), “A Delicate Balance” (Tony Award), and “Three Tall Women” (Drama Desk Award). Mr. Albee’s plays also include: “The Death of Bessie Smith,” “Fam and Yam,” “The American Dream,” “The Ballad of the Sad Café” adapted from the novella by Carson McCullers (Tony Award), “Malcolm” adapted from the novel by James Purdy, “Everything in the Garden,” “Tiny Alice” (Tony award), “Box and Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung,” “All Over,” “Listening,” “Counting the Ways,” “The Lady from Dubuque,” “Lolita” adapted from the novel by Vladimir Nabokov, “The Man Who Had Three Arms,” “Finding the Sun,” “Marriage Play,” “The Lorca Play,” “Fragments,” “Occupant,” “Knock! Knock! Who’s There!?,” “The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia?” (Tony award, Drama Desk Award), “The Play About the Baby,” “Peter & Jerry” retitled in 2009 as “At Home at the Zoo,” and “Me Myself and I.” He received the National Medal of Arts in 1996, a special Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement, the Academy of Achievement’s Golden Plate Award, the Drama Desk Award Special Award, the Edward MacDowell Medal for Lifetime Achievement, and the Pioneer Award for Lifetime Achievement from the Lambda Literary Foundation.

EDWARD ALBEE, recognized by many as one of America’s greatest living playwrights, his many works include “The Zoo Story” (Drama Desk award, Vernon Rice Award), “The Sandbox,” “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” (selected by the award’s grand jury for a Pulitzer, but overruled by the advisory committee – the play received the Tony Award in 1963, and for Best revival in 2005). He is a member of the Dramatists Guild. He has received Pulitzer Prizes for Drama for “Seascape” (Tony award, Drama Desk Award), “A Delicate Balance” (Tony Award), and “Three Tall Women” (Drama Desk Award). Mr. Albee’s plays also include: “The Death of Bessie Smith,” “Fam and Yam,” “The American Dream,” “The Ballad of the Sad Café” adapted from the novella by Carson McCullers (Tony Award), “Malcolm” adapted from the novel by James Purdy, “Everything in the Garden,” “Tiny Alice” (Tony award), “Box and Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung,” “All Over,” “Listening,” “Counting the Ways,” “The Lady from Dubuque,” “Lolita” adapted from the novel by Vladimir Nabokov, “The Man Who Had Three Arms,” “Finding the Sun,” “Marriage Play,” “The Lorca Play,” “Fragments,” “Occupant,” “Knock! Knock! Who’s There!?,” “The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia?” (Tony award, Drama Desk Award), “The Play About the Baby,” “Peter & Jerry” retitled in 2009 as “At Home at the Zoo,” and “Me Myself and I.” He received the National Medal of Arts in 1996, a special Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement, the Academy of Achievement’s Golden Plate Award, the Drama Desk Award Special Award, the Edward MacDowell Medal for Lifetime Achievement, and the Pioneer Award for Lifetime Achievement from the Lambda Literary Foundation.