Willie Ruff

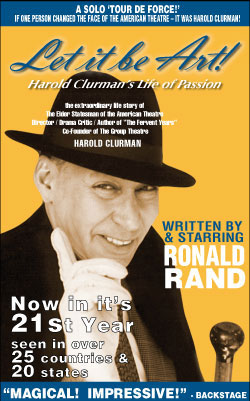

is an American jazz musician specializing in the French horn and double bass and ethnomusicologist, a Yale School of Music professor from 1971 to 2017, founder of the Duke Ellington Fellowship at Yale in 1972, and a writer and educator of wide-ranging interests and influences. Mr. Ruff played in the 766 Army Air Corps Band in Columbus, Ohio among the famed Tuskegee Airmen. For over fifty years, he performed in the Mitchell-Ruff Duo with pianist Dwike Mitchell, playing and recording with many well-known artists including Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Miles David, Sarah Vaughn, and Dizzy Gillespie. From 1955 to 2011, the duo regularly performed in the United States, Asia, Africa, and Europe, and was the first jazz band to play in the Soviet Union in 1959, and in China 1981. Mr. Ruff also recorded with Billy Strayhorn and Lalo Schifrin and was chosen by John Hammond to be the bass player for the recording sessions of “Songs of Leonard Cohen,” Mr. Cohen’s first album, released in 1967. He recorded two albums with Miles Davis — the classics “Miles Ahead” and “Porgy and Bess.” Mr. Ruff is one of the founders of the W.C. Handy Music Festival in Florence, Alabama. He was inducted into the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame, received the Connecticut Governor’s Arts Award, and Yale University’s School of Music Sanford Medal. In 1992, Mr. Ruff published his memoir, A Call to Assembly: The Autobiography of a Musical Storyteller, awarded the ASCAP Deems Taylor Award. Mr. Ruff co-created the documentary, “A Conjoining of Ancient Song,” which received its world premiere screening at Yale in 2013. His work in this area is also a subject of Sterlin Harjo’s 2014 documentary film, “This May Be the Last Time.”

You come from Sheffield, Alabama.

Yes, I was born in there in 1931, in northwest Alabama where W.C. Handy and Helen Keller came from. When I was about three, I’d sing “Saint Louis Blues” for candy in grocery stores, and I got a lot of candy. Music was in the air.

When I was six years old in the second grade, W.C. Handy visited our elementary school. He was a successful music publisher, and a native of Muscle Shoals, and knew one of the teachers. Handy impressed on all us the importance of education.

He told us: “Stay where you are, you stay in school. Get all the book learning all you can, because that’s the only thing that’s between you and the devastation you have inherited. Stand up and acknowledge and protect your beautiful heritage.”

I stood in this little line and I was permitted to shake the hand that wrote the “St. Louis Blues,” and I was never the same boy again.

Did you develop a love of music very early on?

When I was a child I knew a dozen or more people who were way past a hundred-years- old. Some of them were emancipated former slaves, and they told me: “Wherever you go and you’re going to go places away from here, you be sure and tell them you are from Sheffield, Alabama.” And I would sell them newspapers in those days. We were taught not to let anything hold you back.

I’ve come back here, and I bought the land I used to plow with a mule; I felt that connection. I don’t have a mule anymore.

Now, growing up right across the road from where I grew up, there was a white kid, his name was Mutt McCord. He was eleven years old, and older than me. And after school, he would bring his drums out in front of his home and set it up on the lawn and practice. I was really interested but my mama told me: “Don’t you go over that street. You could get run over.”

A car might come along once every week or so, so there wasn’t much of a chance of that happening. So, I went over there, and I hung out with him and he’d play recordings of Count Basie and Benny Goodman recordings, and that’s how I got to learn about that music at an early age.

You also got into the Army at a very early age.

My mama died when I was thirteen, so by the time I was fourteen, I was a little hard up, in dire straits, living on short rations, I had been selling black papers, but there I was with no future in sight and hungry for an education.

It was right after the war, 1946, and segregation was still in full force, and the army was reorganizing itself right after World War II. If you were seventeen and had your parents’ permission, you could enlist. I was playing in the high school band. Now I had a cousin who had been recruited, and he told me if I got in I could have all the food I could eat, and a monthly salary. I said, “How am I going to do that? I’m only fourteen.” He says, “For a musician, you sure are dumb.

So, I told them I was seventeen, and that I had my father’s permission. See, I had to present proof of my age, so I took an affidavit to get it notarized to the guy who had the notary stamp at his store, and he was so busy weighing a sack of onions, he didn’t really look at the paper and just stamped it. I took my affidavit and started my career in music.

When did you first meet Dwike Mitchell?

I met Dwight Mitchell when I re-enlisted my second hitch in the military. He was already well-established in this band in the US Army. There were more than a hundred twenty people in the marching band. We played parades out on the parade field, John Phillip Sousa marches, all from memory.

I knew about this terrific airbase, , and by this time, I think I was sixteen, and I was already playing French horn, so I asked one of the men, “What is the main thing you’ve got here?” They said: “We’ve got a nineteen-year genius, a pianist Dwight Mitchell. He turned out to be a couple years older than me.

Well, that Christmas, I didn’t have a home to go to, so I just stayed on the base, and Mitchell had had a fuss with his father, he wasn’t going home either. So, I was there; there was the two of us. And I picked up a bass fiddle, and he said, “I can show you how to do it. I had a great bass player, but I don’t have a bass player.” He had been discharged.

So, I watched what he did and that was Tuesday. On Saturday, we all played on the radio. We played a lot of things, and I made one mistake, but after that, I didn’t make any more mistakes.

1949, at Lockbourne Air Base, U.S. Tuskegee Army Air Corps Band, all-black Air Force unit

You played with Dwike Mitchell for over fifty years, as the Mitchell-Ruff Duo, until Mitchell’s death in 2013.

Mitchell and I, we first met in 1947, in the 766 Army Air Corps band in Columbus Ohio, I didn’t start out playing the French horn to play jazz. Mitchell and Ruff later played in Lionel Hampton’s Band, but we left in 1955 to form our own group.

We had a fabulous stroke of good luck, playing in gin mills and made some records and one night we played in Birdland opposite Count Basie, and there was the two of us, we were a group that could play three instruments, so that made us very affordable to book. So, we were able to open for Louis Armstrong, Lena Horne, Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie, we opened for Duke Ellington. That was our world at that time.

Willie Ruff and Dwike Mitchell – Mitchell Ruff Duo

What led you to want to go to Yale?

I was in the army, it was around 1949, and I happened to read an interview with Charlie Parker in a jazz magazine, and he was asked: “Bird, if you could do whatever you want to do with your life, what would that be?” He said: “ He said. That’s easy. There’s a cat whose music I’ve heard and I read his writings and I’m fascinated and if I had my druthers, I’d go and find him and I’d sit at his feet and learn me some music because he’s teaching at Yale.” He was crazy about this man. His name was Paul Hindemith.

Well, I had never heard of him. I was in the Air Force for over three years, and I was trying to decide where I could use the windfall that I had received from the U.S. Government’s GI Bill, and I really didn’t know anything about music and I thought if Charlie Parker thought he’d sit at his feet, I said to myself: “It’s time to start my education.”

So, I applied at Yale and they sent me an invitation. I brought my French horn and played an audition, and by some miracle, they let me in! So, Uncle Sam put me through my schooling!

Pretty soon after that you played with Benny Goodman.

Mel Powell, he was a prodigy, and he had come to study with Paul Hindemith, and Benny Goodman comes to town. And I was playing in the New Haven Symphony, so I’m eighteen, and Benny Goodman comes to town. And I’m sitting at the horn, playing in the orchestra, and Mel Powell comes out with Benny Goodman, and Mel spots me in the horns section and he says to Benny, “The guy in the horn section is a bass player, let’s invite him up to play.” Mel and I had been playing around town. So, there I got to play with Benny Goodman at eighteen years of age at the Yale Bowl, and that lead to more work as a bass player.

When you studied with Prof. Paul Hindemith, what was he teaching in your classes?

When you studied with Prof. Paul Hindemith, what was he teaching in your classes?

Paul Hindemith was a classical composer and he was my professor at Yale. He was the reason I went to Yale. The first thing he did was he taught a class about the history of the theory of music, to understand the origins of music science, and he was talking about the composer soloist. He wanted the students to know about Kepler’s obsession in the 1600’s, with music in planetary motion, and Kepler had discovered the three laws of planetary motion, and he also challenged the musicians of his time to show him where these harmonic relationships are in the march of the planet’s march around the sun.

What Kepler was pointing out in the 1600’s nobody could measure these things yet, the technology hadn’t been invented. But between the time I was a student of Hindemith’s at Yale and the time I had been invited back to teach; something had happened.

The computer had been invented and it became possible to build this planetary computer for the ear that Kepler wanted us to have. So, I found people at Yale, one was one of the great geologists and another was one of the greatest mathematicians there, and I put them together, and they were able to make this planetarium for the ear.

And you remained at Yale for quite a while.

At Yale, I taught for forty-six years and had them fooled I knew what I was doing. I didn’t teach that often. I taught one class a week on Friday mornings.

When I was invited to Yale, they needed to take a fresh look at what music was about, and they asked me what I wanted to teach. I told them that I was really interested in using media and music as a way to get music into schools. So, I organized the Duke Ellington Fellowship Program to bring famous musicians like Duke Ellington to our campus. We had Dizzy Gillespie come, and Eubie Blake, Charlie Mingus, and it was just great.

You also discovered links between traditional black gospel music and unaccompanied psalm singing.

See, I began to study the cross-cultural phenomenon of congregational singing and I decided to follow up a friend of mine, Dizzy Gillespie’s claim that some remote African- American congregations in the South were actually singing hymns in Gaelic.

When I studied The Massachusetts Bay Colony Psalm Book from 1640 in Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, I found that the form, in which one church member calls out the first line of a psalm and the rest of the congregation continues to chant the text in unison, had been a common worship practice in colonial America.

This call-and-response service had been chanted by descendants of African slaves in the American South, and by white congregations in remote churches of Appalachia and it was still being intoned in Gaelic in its original form in Scotland’s remote and culturally-isolated Outer Hebrides. See, I also trace my own lineage back to the crossroads of races and cultures that embrace this custom.

So, in 2005, I organized an international conference at Yale, and we were able to bring together a few of the almost-extinct congregations still practicing the ancient line-singing tradition. We brought together The Free Church Psalm Singers of the Isle of Lewis from Scotland, and the Indian Bottom Old Regular Baptists from southeastern Kentucky; and we had the Sipsey River Primitive Baptist Association, they had come from Eutaw, Alabama.

And the congregation members came to Yale to perform in a shared service that had adapted over generations.

Now as we went along, I also learned that the tradition extended to the Muskogee Creeks in Oklahoma so two years later, I organize a second conference at Yale, and we were able to bring together gather Native-American, African-American, and Appalachian line-singers together for the first time.

Scholars from Yale, York St. John's University in Scotland, Rogers State University in Clairmore, Oklahoma, and other institutions came to Yale to explore the history and migratory trajectories of the ancient but endangered form of Protestant congregational singing.

First International Conference On Line-Singing organized by Willie Ruff held at Yale University

And the Indian Bottom Old Regular Baptist Association from southeast Kentucky and the Sipsey River Primitive Baptist Association from Alabama returned, and this time, the white Appalachian and Deep South African- American line-singers sang with congregants of the Hutchee Chuppa Indian Baptist Church from Oklahoma, who intone the ancient Scots liturgy in their native language.

And the Indian Bottom Old Regular Baptist Association from southeast Kentucky and the Sipsey River Primitive Baptist Association from Alabama returned, and this time, the white Appalachian and Deep South African- American line-singers sang with congregants of the Hutchee Chuppa Indian Baptist Church from Oklahoma, who intone the ancient Scots liturgy in their native language.

For the first time ever, Native American Baptists who originated from Alabama and Georgia sang with their black and white counterparts in an academic setting to learn about the origins, background, similarities and differences in the singing heritage they share.