Robert Perry

Storyteller, Historian, Artist, and the Author of six books. He has served on the Board of Directors of the Wordcraft Circle of Native Writers and Storytellers. Before moving to Alabama, Mr. Perry served as Vice-Chairman of the Council of Elders that advises the Chickasaw Nation on cultural issues. At the 1966 tribal meeting, Robert Perry was elected to the Chickasaw Advisory Council by a show of hands. He rose to Chairman, when in 1977 the tribe’s constitution was approved by the U. S. government. Tribal leaders could be elected, and a tribal complex built to form businesses. By 1993, Robert Perry served five years as chairman of the board on the Chickasaw Industrial Development Board. A retired chemical engineer, Mr. Perry holds eight U.S. patents. He chaired the City of Sheffield’s Port Authority to develop Tuscumbia Landing, a water site on the national historical Trail of Tears. He also does re-enactments and joined the American Indian Alaskan Native Tourist Association, the only National organization that promotes international tourism to Indian Country. Along with his wife Annie Perry, he works with the Natchez Trace Parkway Association (NTPA) to teach school children about Chickasaw culture and history through living history. In 2011, he was inducted into the Chickasaw Hall of Fame.

Storyteller, Historian, Artist, and the Author of six books. He has served on the Board of Directors of the Wordcraft Circle of Native Writers and Storytellers. Before moving to Alabama, Mr. Perry served as Vice-Chairman of the Council of Elders that advises the Chickasaw Nation on cultural issues. At the 1966 tribal meeting, Robert Perry was elected to the Chickasaw Advisory Council by a show of hands. He rose to Chairman, when in 1977 the tribe’s constitution was approved by the U. S. government. Tribal leaders could be elected, and a tribal complex built to form businesses. By 1993, Robert Perry served five years as chairman of the board on the Chickasaw Industrial Development Board. A retired chemical engineer, Mr. Perry holds eight U.S. patents. He chaired the City of Sheffield’s Port Authority to develop Tuscumbia Landing, a water site on the national historical Trail of Tears. He also does re-enactments and joined the American Indian Alaskan Native Tourist Association, the only National organization that promotes international tourism to Indian Country. Along with his wife Annie Perry, he works with the Natchez Trace Parkway Association (NTPA) to teach school children about Chickasaw culture and history through living history. In 2011, he was inducted into the Chickasaw Hall of Fame.

Did you have any idea growing up in Ada, Oklahoma that you would become a historian storyteller of American Indian culture?

As an American Indian, what I do is to help others. So much of what the elders share has been lost, like the dark ages. I learned a lot from my grandmother. She was very smart and lived to be a hundred years old. Once grandmother made us brothers stop playing. Wearing her serious face, she told us that as a people we had to remain strong because of who we are as a nation. Be proud you're a Chickasaw. [silence] We were just kids.

As I grew up, I realized her words to us meant if everyone gives back, the tribe will remain strong. My earliest recollection of what I wanted to do as an adult was at age twelve years old. We lived three blocks from the public library. School recessed for the hot summer. Every day when the doors opened, I went from one shelf to the next, reading until the doors closed. It was the only air-conditioned building in town.

I wanted to be a medical doctor but couldn’t afford the education. Over the summer, my mind was made up – I was going to become a chemical engineer. I lived in a small town; no one knew enough to discourage my final choice.

I easily memorized the national geography of every country in the world and all the state capitals. I could visualize them. I could see around things; I understood I had a unique vision and could ‘travel the world’ – by my imagination; I needed to be free as a bird. That thought resonated more than anything else. It helped me realize with good vision, and memory, and persistence, I could do anything.

Our family didn’t have much money, and usually didn’t eat much from Thursday until Monday. We got by. There were two tools in the house, a claw hammer and a long screwdriver with a rounded end. You saw what needed to be done or built and did it. I was used to living in the dirt.

When I graduated from high school, Dad said: “Boy, I can’t send you to college anywhere. My suggestion is to join the Army. They’ll pay you instead of you paying them.” He knew I’d find a way to get through college.

On college graduation day, he made the long trip to the ceremony. He gave me a ten-dollar bill. For him, that was a lot of money; his education ended at the 8th grade at an Indian Vocational School. There was nothing else but go to work. He was a full blood Chickasaw and fluent speaker but never around his children. I asked if he’d teach me the language. “No. Boy, you need to get an education and leave, get some skills and come back and help your tribe, then you can learn to speak Chickasaw.”

My father’s Dad when he was a young boy, about a dozen years old, was found wandering in the woods. He was walking fifty miles to an uncle’s house. His parents had died, and the Chickasaw woman who found him was a cattle rustler. In those days, everything was kept ‘close to the vest.’ We knew nothing about our ancestors.

The rest of my life I spent trying to establish our family history. By tribal custom, a child without parents would be raised by kinfolk. There were no orphans. I didn’t know the woman who raised him was kinfolk. The tribal roll listed her mother’s name and she was also listed on the first Chickasaw census of 1818. She had married a Choctaw named Perry, who died early.

When did you decide to become a storyteller?

I retired in the 1980’s, and wanted to do something fun and non-technical, so I would become a storyteller, a teller of Indian tales. My civilized tribe didn't have ancient stories or I, a newly retired engineer, didn’t know a traditional elder to ask. Oklahoma has thirty-nine Federally recognized tribes so I would ask their elders. It was easy to find an audience for free, but there was a problem.

Oklahoma has three hundred thousand Indians that grew up hearing stories and wouldn’t pay for a story they could get for free. Other storytellers who had walked this path advised me to write a book of stories to sell. Two Native generations had been steered from traditional culture, but their grandchildren wanted to know, and a book makes this possible.

One time, I was in a sweat lodge ceremony with the Indians of the Delaware tribe. Sweat lodge is a group prayer to the Creator, where I expressed my desire to be a storyteller. The elder prayed for my strength and energy, long memory and long life.

Coming from a Delaware elder, his trust was vital. Trust is important to Indians because of the ways they have been mistreated. When my tribe was not a resource of old stories, it was a blessing to be trusted enough by other tribes to share stories.

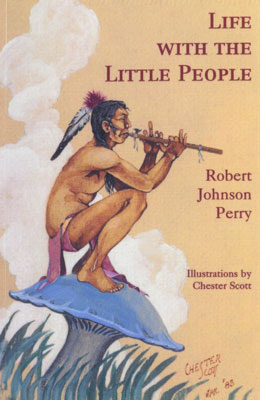

I began to talk with elders. I was so hungry for stories. I was told: “You need to meet ol’ Chester, a pure-blood Creek Indian, he knows all the stories. The word “ol’ means venerated, not elderly.

When I found Chester, he was ‘holed-up’ in a dark room. Fifteen years before, he had exercised too soon after hernia surgery and the sutures ripped out. He looked bad and vowed never to leave the dark room. Chester was a trained artist but gave up.

When I asked him to tell me: ‘little people’ stories, Chester reminded me the stories were sacred and not told to others. “Why you?” He let me suffer a moment, then he said, “I’ll tell you the stories...but only if you can locate a patron who used to buy my art.” Success would be the test that the ‘little people’ accepted me.

In three weeks, I tracked down Frankie, who agreed to call Chester. She had moved to three different states, married three different men. The phone call delighted Chester. He had sold images of ‘little people’ to non-Indians, but the taboo kept him from giving away secrets. If I wrote a book about them’ that protected their secrets, it would be good to teach children.

So, Chester would tell his stories, once. No recorders, because little people don’t like technology. His stories were short family tales. I could write the story any way. I spent the next year learning a little of the Creek language and fitting his great grandma inside a history of the times so readers would understand. Chester never wanted to read my work but drew pictures for each chapter.

Why is storytelling so important for you?

There was no written Chickasaw language; communication was oral with lots of gestures. Sound gives your position to enemies.

When I stand before a group of people, I don’t start talking until every eye is looking at me. This intense focus on me has been difficult because all my life, I can’t talk about myself very well. But wearing the ‘mask’ of a storyteller, I can share the stories. The mask has helped communication more than anything else in the last thirty years. Today we live at a very hurried pace; in the only ‘time outs,’ we need to awaken and revitalize senses.

The importance of storytelling lies not in the creative ability of the storyteller, but in the community created by the story. For the traditional storyteller, each story evokes the shared experiences of a people. Things might get done faster through email, but storytelling is a sacred endeavor, especially in Native American culture.

If a story isn’t told, it dies. Stories are important for an elder to talk about and I can assure, this isn’t done for money. When I meet with Indians of any tribe in the world, they will trust me because I have this interest in our communal history. Charlie Soap, who is in your book, CREATE! knows who he is because of his history. We’re all connected through our history.

Robert and Annie Perry

You’ve also told stories through re-enactments on the Natchez Trace.

The Natchez Trace was the first Federal highway from Nashville to Natchez. The trace or trail passed through Chickasaw land in Mississippi. I was recruited by the Natchez Trace Parkway Association to tell stories along the Trace.

Since moving to Alabama, I have done re-enactments and told stories to students at different schools and outdoor gatherings. I dress as a Chickasaw of 1820 and tell about the regalia. I was invited to the Hermitage, Andrew Jackson’s home, to show how the Chickasaws fed the starving soldiers returning to Nashville in 1814. I think it's important that we share these stories.

There’s a ‘hook,’ a way to capture people’s imagination with these stories. At McFarland Park in Florence, Alabama, loads of people came for an outdoor theater event at a Chickasaw village. It rained most of the day and the Tennessee River was near flood stage. We did a re-enactment with forty-two Choctaws, a keelboat with crew, and men dressed as soldiers; we all came together to see history of what had gone on before. That’s what’s capable of outdoor theater.

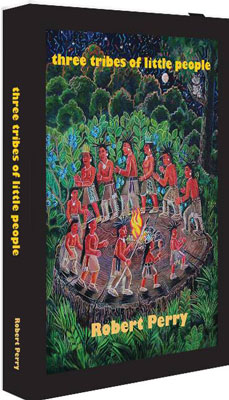

One of your books, Life with the Little People, represents stories found in the oral traditions of American Indian cultures. You write about the “little people” – ‘a tiny people with big hearts, often invisible to non-Indians and adult Indians, impish in nature, and often envisioned as caretakers,’ contributing to the well-being of Native People. And your sequel, Three Tribes of Little People, describes how the Chickasaws, Choctaws, and the Irish Peoples were all brought together by the Little People of the Indians and the Leprechauns of the Irish who brought with them healing and fun. Most of the stories in the book came from the life of Sebena Burris, a Chickasaw-Choctaw elder. The Indians also seem to have much in common with the Irish people, but also with the native people in the north of Sweden, Norway, Finland and Russia - the Sami people, in the region they call Sápmi.

According to oral tradition, Little People existed in the forest and taught young people about the healing medicine plants. They have existed for a very long time. I was invited to speak about the little people to a convention of medical doctors seeking alternative ways to treat patients. They wondered how Indians were kept well with medicine plants and without hospitals.

According to oral tradition, Little People existed in the forest and taught young people about the healing medicine plants. They have existed for a very long time. I was invited to speak about the little people to a convention of medical doctors seeking alternative ways to treat patients. They wondered how Indians were kept well with medicine plants and without hospitals.

You wrote: “In American culture, the imaginary is too often dismissed as the unreal. Yet, if the current trends in popular culture have a lesson to teach, the lesson may be that the imaginary appears more tangible than the real. Indeed, the advent of virtual reality suggests an adult desire to return to the world of the imaginary friendships experienced in childhood.”

Imagination is the best part of ourselves we have as human beings. I like to use humor. This is a way to be ‘in service,’ to survive – by bringing laughter. You can laugh, even through pain and suffering, just as they did on the Trail of Tears to survive.

When I was in the 5th grade, Dad moved to Oklahoma after WW2 to oversee the family Indian land. In those days, he worked six days each week. I had never heard him laugh until moving to Ada. We were walking down main street and Dad stopped to talk to brown-skinned men that we met. They were talking in Chickasaw and what struck me were the belly laughs. My Dad laughing! You could hear their laughs echo down the street – and in my mind forever.

I could see that belly laughs sealed the story inside. I learned that if you can get someone to laugh at your story, they will never forget that story. This is why the Chickasaw never had a written language to remember. It probably goes all the way back to Adam and Eve.

I could see that belly laughs sealed the story inside. I learned that if you can get someone to laugh at your story, they will never forget that story. This is why the Chickasaw never had a written language to remember. It probably goes all the way back to Adam and Eve.

How would you describe the “black drink” of the Chickasaw?

The “black drink” is a concoction of different cassena plants, a yaupon holly, which is passed around as a communal bowl before you fast during a ceremony which lasts until a second sunrise. You drink it before playing stickball. The timing is important for the drink to purge you – to help you throw up your guts. Stickball is an endurance game, played without pads. After the purge, you don’t feel pain from a whack with a hickory stick and you can keep on playing.

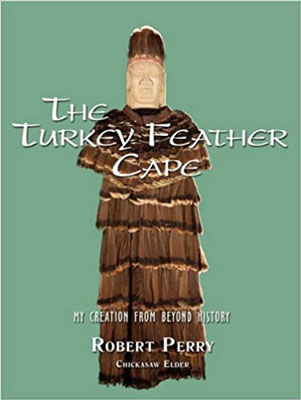

Another of your books is The Turkey Feather Cape: My Creation from Beyond History.. You spent eight years on the board of the Chickasaw Historical Society and used your research and skills to determine how the Chickasaw artisans four hundred years ago made a turkey feather cape and tapped his artistic abilities to create one. The Turkey Feather Cape you made is on permanent display in the Chickasaw Cultural Center in Sulphur, Oklahoma. You have also used your artistic abilities through glassblowing to make a conch shell which replicated ancient Black Drink cups. The glass conch won Best of Show at the Chickasaw Annual Art Show. From then on, the Art Show included advanced contemporary artwork. Why did you want to re-create a turkey feather cape?

It was a challenge. The Chickasaw Nation was building a giant cultural center and the director, Sue Linder, said to me: “You're an elder. I want you to make a turkey feather cape.” Sue knew, and I knew, this would be the first one made in hundreds of years. I said, “I'll make it, but what’s more important is to teach others because there is no history about the feather cape, or how it was made.” The art of making the feather cape was lost.

So, I began research for the next two years. The explorer, Hernando de Soto had seen the feather cape in the 1540’s during his expeditions. I asked archeologists if any artifacts were found back to AD 1000. Feathers in the earth don’t survive, but the twisted bark netting to attach feathers did. The archeologists knew some cases that Native Americans had been able to understand how a thousand-year-old artifacts were used, so I had free-range and few facts to go on.

The Ancient World was divided into lower, middle, and upper levels. We live in the middle and the Creator above. Birds are the messenger to the Creator. Those chosen to wear the feather cape could communicate with the upper world. De Soto’s men killed a chief wearing the feather cape, so he believed as did his followers that the feather cape was spiritual armor. His demise is why the feather cape didn’t survive.

Chickasaw hunters brought their turkey kills for me to pick feathers. Once the materials were in hand, Sue wanted me to write a book telling how the cape was made. This predated the Cultural Center being built, so there was no money for the book. I had to figure out how to self-publish.

It took three months of eight-hour days to put together the cape. Every feather, there were seven hundred and eighty-three, was hand-tied and I came up with inventive ways to overcome difficulties I encountered. I could visualize an artisan long ago who specialized in making feather capes. Following in his footsteps was empowering regardless of the time required.

It took three months of eight-hour days to put together the cape. Every feather, there were seven hundred and eighty-three, was hand-tied and I came up with inventive ways to overcome difficulties I encountered. I could visualize an artisan long ago who specialized in making feather capes. Following in his footsteps was empowering regardless of the time required.

Was there a reason you chose to use a wooden head piece to go with the feather cape?

I planned to enter the feather cape in the Chickasaw Art Contest but finished the cape three months early. So, with time on my hands, I felt something was needed. Something inside me spoke, “Only a wooden head will do.” The things I do, I do as an elder to benefit others.

I had this bad dream. I was fighting with a giant cave bear and he was getting the better of me. I woke up in a sweat. The next night the battle continued. The bear said, “I want you to do something. You – make a bear claw necklace.” I told him that a bear would be killed for the claws. The bear replied, “No. You – make glass bear claws and use imitation fur. Humans will no longer kill bears.”

So, I learned glassblowing. The first project I made was to hollow bear claws colored-black with holes to string the claws and then to wrap with fake fur. The feather cape and bear claw necklace won 1st and 2nd prize in textiles in the Contest.

So, I learned glassblowing. The first project I made was to hollow bear claws colored-black with holes to string the claws and then to wrap with fake fur. The feather cape and bear claw necklace won 1st and 2nd prize in textiles in the Contest.

The art contest organizers invited me to create more glass blowing artworks for the following year. I continued making shapes with a team of glass artisans to learn the craft. Blowing glass before a fiery hot oven with other artisans is like dance choreography; it is done without words. My masterpiece was the black drink conch shell with three colors. It won the grand prize.

In my Feather Cape Book, it tells stories of six men and six women who were honored with turkey feather capes. The six women were like encyclopedias of where to find medicine plants. When a child’s disease failed all cures, the parents asked what could be done. The women believed that the blooms of the yellowwood tree could heal. The trees bloom once every six years but bloomed last year. The Chickasaw warriors traveled long distances and knew where yellowwoods grew and bloomed. “Go,” they were told to find the Arkansas tree and bring the blooms to cure the disease. This kind of story never dies out.

What continues to be your greatest challenge in keeping the fire burning, letting people know about “Tuscumbia Landing,” in terms of language and storytelling?

By recognizing that Tuscumbia was unique as a community. Tuscumbia was situated on lands that had been Chickasaw, and the town had been named for a Chickasaw Warrior, a veteran of the War of 1812.

Now what’s special about Tuscumbia is that the town residents provided food, clothing, and hospitality to the migrating Creek Indians in 1828. Tuscumbia was the only town in all of Alabama and Georgia to welcome a bedraggled people. The Creek Indians were put on steamboats at Tuscumbia Landing two miles away and hauled to Indian Territory. Tuscumbia has a legacy of hospitality to Indians, but not many understand that today.

Impassable rapids prevented steamboats going further up the Tennessee River, so they docked at Tuscumbia Landing. The government plan was for the Indian Removal to be quick, and the mass movement was by steamboat. There were twelve Creek migration contingents and nine came through Tuscumbia and Tuscumbia Landing.

The 1838 Cherokee removal came after the Creeks. The Cherokees were captured forcibly and imprisoned. Two contingents came through Tuscumbia Landing before a hundred-year drought dropped the river level, which was too low for boats. The Cherokee Chief got approval to walk what is today is the historic National Trail of Tears; the many trails cover five thousand miles through nine states.

What remains your most important goal as you go forward?

Tuscumbia Landing is a Trail of Tears site. The National Park Service has developed a charette, a development plan for the site. They are working with the Trail of Tears Association and Cherokee Nation to implement the NPS plan. As we go forward, we will continue working with Native storytellers and historians to collect and preserve the stories and tales from the Indians of the Southeast United States.

Tuscumbia Landing is a Trail of Tears site. The National Park Service has developed a charette, a development plan for the site. They are working with the Trail of Tears Association and Cherokee Nation to implement the NPS plan. As we go forward, we will continue working with Native storytellers and historians to collect and preserve the stories and tales from the Indians of the Southeast United States.

At this time of life, I have no need to build a resume. Nonetheless, I will cite a project that I hope will honor the ancestors. I was invited to National Park Service event to honor several Indian educators for “above & beyond.” They had published curriculum guides honoring the forty tribes that helped the Lewis & Clark Expedition survive. Their work is now accepted in three states.

We met and they immediately wanted to help by developing a curriculum that could be used across all states to teach students about the Trail of Tears. I am working as a strategic planner with this group and a regional archive.

Our demonstration report describes how a curriculum could be built for all the Trail of Tears tribes. The State of Arkansas has organized a group of trainers to integrate the demonstration report into Arkansas schools. It’s a huge undertaking and we're continuing to work on the curriculum design.

This is a time for me to appreciate longtime friends and the grandchildren. But as an elder, I still question: “How do you remind people what matters?”

People know I’m from Oklahoma’s tornado alley and they ask me, “Why don’t you worry about tornadoes?” Of course, I pray the tornado will not harm us. But you must have faith and know what will work and bring comfort and strength. Here in Tuscumbia, tornadoes veer away.

The Taos war chief explained that I have a big blue aura around me, as do my two children. He explained that people who can see auras know this is a person of peace. Wherever we go, we accept the aura is with us. Probably, everyone has an aura of some color, big or small.

You also traveled to South America as an elder.

I was invited to Chile by a group to help the Mapuche Indians who lived six hundred miles south of Santiago, The Mapuche are individuals and not so much a tribe because the government doesn’t want to recognize and protect a tribe. Here in America, U.S. tribes are sovereign nations.

The Mapuche are very poor and live behind tall fences in tiny self-contained villages. Before my hosts could announce me at their gate, the leader gestured to enter; he pressed his heart to show he knew that I was okay. He knew nothing about me.

Raising food was important. I brought heritage Chickasaw corn and showed how to plant the three sisters: squash, beans, and corn. We were fortunate to be close to one another, the primitive man depends on his heart over his intellect.

The Mayan calendar ended about twenty years ago, but I am sure the Indian people kept on living. I always wanted to talk heart to heart with the Mayans, as I did with the Mapuche. The Mayan culture was so advanced, but everything was lost in 800 AD – or could it be rediscovered? Hmm. •